Hopfield Networks

December 22, 2025

Introduction

In my previous post, I provided a quick introduction to Energy-based modeling (EBM), which is an alternative approach to maximum likelihood estimation. Obviously, much of the concepts in EBM are borrowed from Physics (specifically, thermodynamics). Thus, it is not a surprise that early attempts of generative modeling or machine learning also came from physicists and pure mathematicians.

In this post, I am keen to introduce the concept of the Classical Associative Memory (AM) systems, also commonly known as Hopfield networks. Such systems, derived from Ising models, were first introduced by Shun’ichi Amari in 1972, and rediscovered and popularized by John J. Hopfield in 1982. In recent times, both individuals have finally received big accolades for their achievements. For examples, Amari received the Kyoto Prize in 2025 and Hopfield received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2024.

Nonetheless, I would like to emphasize the following point: the introduction of AM systems truly had helped pave the way for more advance generative models, e.g., Boltzmann Machines and even diffusion models (which were also introduced by physicists). Although these networks were elementary, their fundamental concepts are still being applied even in today’s sophisticated deep learning models.

Recurrency via Energy Minimization

To begin, Hopfield networks were the earliest Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Energy-based models, and working examples of generative modeling. Specifically, one can generate new patterns1, and even perform pattern recognition or recovery. For example, you can provide a perturbed example and the model can effectively denoise or fill in the missing blanks of the pattern. This particular process is accomplished via energy minimization, or simply performing gradient descent on a global energy function:

\[E(x) = -\frac{1}{2} x^\top W x,\]where \(x \in \{\pm 1\}^N\) is a binary variable in which we evolve (or update) over time and \(E(x) \in \mathbb{R}\). Meanwhile, \(W\) is our memory matrix obtained via

\[W = \sum_{\mu = 1}^K \xi^{\mu} (\xi^{\mu})^\top,\]which is a summation over all of the dot-products of each pattern \(\xi^{\mu} \in \{\pm 1\}^N\) to itself that we want the system to memorize2. This particular way of forming \(W\) is typically seen as performing Hebbian Learning.

Memories and Fixed Points

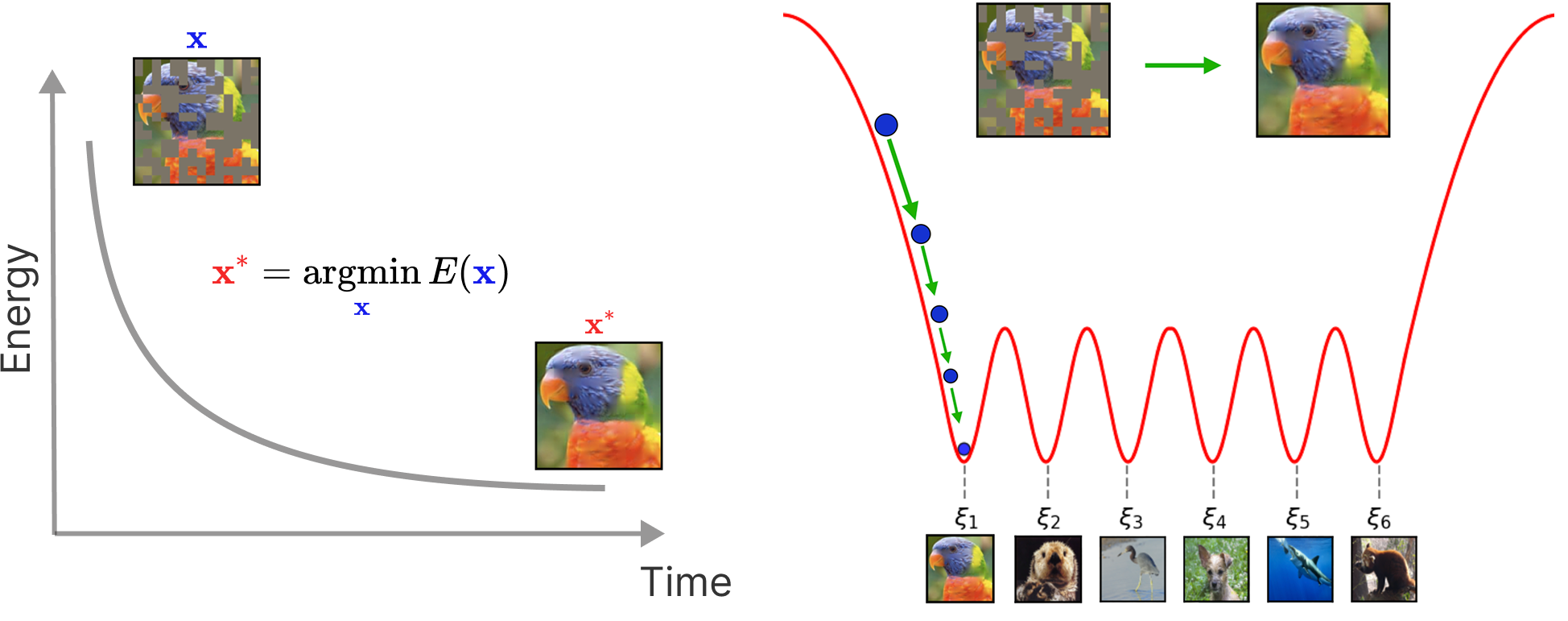

In order to make usage of this system, we simply query the system and perform gradient descent such that we update our dynamical variable \(x\) with \(\nabla_x E(x)\):

\[x^* = \underset{x}{\text{arg min}} \,E(x)\]where hopefully the system converges to equilibrium such that \(x^* = \xi^* \in \{ \xi^{\mu} \}_{\mu = 1, \dots, K}\) is a memory stored inside of our Hopfield network. In other words, our memories (stored inside of the AM network) are simply local minima of the energy function \(E(x)\), which the system will converge to, given a query \(x\)3.

This aspect is the main distinction between these networks and the typically mentioned RNNs. Particularly, recurrency happens via energy minimization, while in typical RNNs, recurrency occurs by treating an input as a sequence (akin to performing a 1-dimensional convolution operator).

Spurious Patterns: The Duality of Forgetting

So, what happened to these models?

It turned out that Hopfield and others found that these classical AM systems were not capable of storing many patterns. Specifically, Hopfield et al. empirically measured that these networks can only store \(K^\text{max} \approx 0.15N\) patterns, in 1982. This was later formalized, in 1985, using statistical mechanics techniques by Amit et al., demonstrating that beyond this threshold, the probability of successful memory retrieval decays rapidly due to interference between stored patterns and provided an analytical memorization capacity of \(K^\text{max} \approx 0.14N\) patterns.

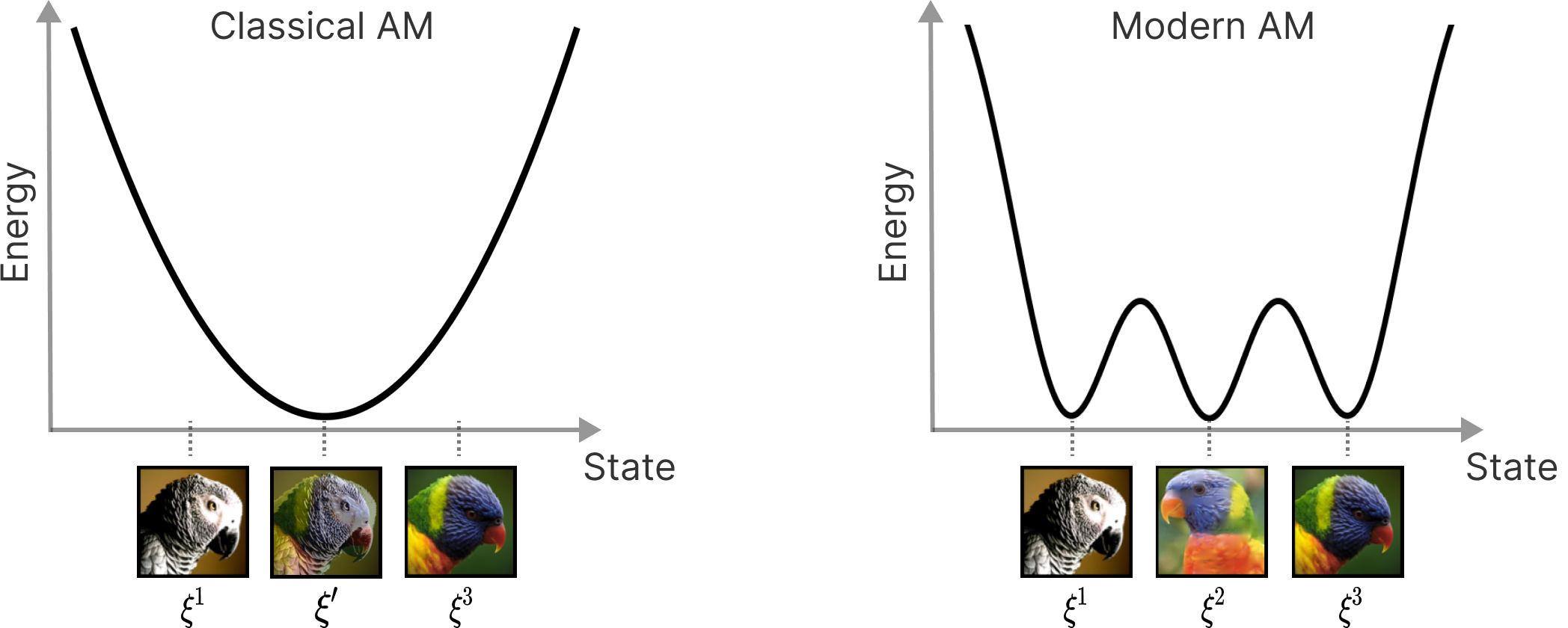

Thus, when the number of patterns \(K\) exceeds \(K^\text{max}\), new local minima of the energy function are formed. Such patterns are commonly known as spurious patterns, depicted as \(\xi'\) in Figure 2. They appear when the memory or storage capacity is exceeded and effectively, hinder the effectiveness of the memory retrieval capability of these AM systems. Funnily enough, although spurious patterns do hinder memorization, we found them to be initial signs of generalization in generative diffusion modeling.

In year 2016, Krotov and Hopfield found that one can apply an activation (or interaction) function on top of the dot product in \(E(x)\), which sharpens the basin around the stored patterns and lessens their interferences among each other, leading to super-linear or even exponential storage capacity for uncorrelated patterns. These modern variants of AM systems are now known as Dense Associative Memories, which I will introduce and discuss more on a separate post.

Conclusion

Overall, these systems provide an elegant platform to perform interesting studies and developments. For examples, one can study how a dynamical system memories and generalizes, as my collaborators and I did in this work, or even design new neural architecture, like we also did here. Nonetheless, despite the recent recognition, I still think this particular topic is unpopular among the practioners, while popular among the theorists of machine learning. I hope this fact will change as there are many interesting things yet to be discovered with these particular models.

References

-

Learning Patterns and Pattern Sequences by Self-Organizing Nets of Threshold Elements . Shun’ichi Amari.

-

Neural Networks and Physical Systems with Emergent Collective Computational Abilities. John J. Hopfield.

-

Storing Infinite Numbers of Patterns in a Spin-Glass Model of Neural Networks. Daniel J. Amit and Hanoch Gutfreund.

-

Dense Associative Memory for Pattern Recognition. Dmitry Krotov and John J. Hopfield.

-

A Learning Algorithm for Boltzmann Machines. David H. Ackley, Geoffrey E. Hinton, and Terrence J. Sejnowski.